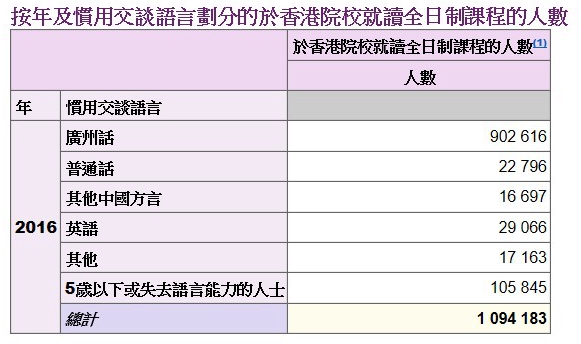

According to the Hong Kong Government Statistics (2016), there are 1, 094, 183 full-time students, from kindergarten to university, in Hong Kong by 2016. As shown in Table 1. Among the full-time students in Hong Kong, Cantonese is the most popular language for communication. There are 902, 616 speakers, followed by English speakers (29,006) and Putonghua speakers (22,769).

Table 1. Communicative language used by full-time students in Hong Kong (Hong Kong Government, 2016)

As for full-time students from ethnic minority groups in Hong Kong, there are 6,528 Indian students, followed by Pakistani students (6, 059), Nepalese students (3, 809), Filipino students (3,370), Thai students (513), and Indonesian students (288).

Table 2. Ethnicity of full-time students in Hong Kong (Hong Kong Government, 2016)

English pronunciation features of the major ethnicity groups in Hong Kong are summarized in the following sections.

Philippine

For Philippine English, the phonology of which was described based on social class variation (Tayao, 2004). Speakers in Philippine were classified into 3 groups, acrolectal, mesolectal, and basilectal (Llamzon, 1997). Speakers from different groups have both common and different phonological features (Tayao, 2004). The voiced stops /b/, /d/, and /g/ are consistently prevoiced when they are in onset position, and /s/ and /z/ may sometimes neutralize in coda position (Lesho, 2018). Speakers in the basilect and mesolect group do not aspirate /p/, /t/, and /k/, while they are aspirated by speakers in the acrolect group only. /tʃ/ is usually pronounced as /ts/, and /dʒ/ as /dj/ word-initially or /ds/ word-finally (Tayao, 2008). The substitution of /p/ for /f/ is common, and /θ/ and /ð/ are sometimes stopped to /t/ and /d/ (Hiramoto, 2011). As for vowels, /æ/ is often merged with /a/. Lacking /æ/ and/or /ʌ/ and merging tense and lax vowel pairs are two common situations among speakers from mesolect and basilect groups (Tayao, 2008). For /eɪ/, all speakers had a slight offglide in the direction of /i/ (Lesho, 2018).

India

In Indian English, /w/ is pronounced as /v/. When pronouncing the word "wet", it sounds like "vet" (Jenkins, 2009). /p/ and /f/ are not distinguished; similarly /s/ and /ʃ/. The alveolar consonants (/t/, /d/, /s/ /l/, and /z/) are retroflexed and become /ʈ/, /ɖ/, /ʂ/, /ɭ/, and /ʐ/. The /r/ sound tends to be a flap /ɾ/ or even be retroflexed flap /ɽ/ (Trudgill & Hannah, 2008). Using voiceless final consonants to replace the voiced consonants is a feature of Indian English. Words like "feed" and "gave" will be pronounced as "feet" and "gafe" (Jenkins, 2009). The voiceless consonants /p/, /t/, and /k/ tend to be unaspirated (Trudgill & Hannah, 2008). Pronouncing voiceless consonants without aspiration is also a feature of speakers of Malaysian English (Jenkins, 2009). As for vowels, preceding /j/ and /w/ are inserted before initial front vowels and back vowels respectively ("eight" /eɪt/ tends to be /je:t/ and "own" /əʊn/ tends to be /wo:n/) in southern India. A preceding /ɪ/ is inserted before initial consonant clusters (/sk/, /st/, and /sp/) in northern Indian, for example, "speak" /spi:k/ tends to be /ɪspi:k/ (Trudgill & Hannah, 2008). In addition, Indian English has a reduced vowel system. Speakers pronounce /ɑ:/ without the length and diphthongs (/eɪ/ and /əʊ/) tend to be monophthongal (/e:/ and /o:/). Both /ɪ/ and /i:/ tend to be /ɪ/; /ʊ/ and /u:/ tend to be /ʊ/ (Jenkins, 2009). There are no stressed vowels and unstressed syllables, for example, suffixes, tend to be stressed in Indian English (Trudgill & Hannah, 2008).

Malaysia

The vowels of Malay speakers tend to have equal duration (Zuraidah, 1997). Long vowels tend to be realised as short vowels, for example, /u:/ tends to be [u], and /Short vowels, before /n/, /l/, /r/, /s/, and /ʃ/, are lengthened in Malaysian English, for example, /ɪ/, /ə/, and /ʊ/ tend to be realised as /i:/, /ɜ:/, and /u:/. "Fish /fɪʃ/" is pronounced as /fi:ʃ/. Vowel reduction is not common in Malaysian English. A full vowel is usually used to replace schwa, for example, "assess /əˈses/" will be pronounced as /æˈses/. For diphthongs, they have a reduce quality (/eɪ/ [e], /əʊ/ [o]), for example, "mail /meɪl/" will be pronounced as /mel/ (Mesthrie, 2008). As for consonants, /tθ/ and /dð/are often used by speakers of Malaysian English so that "thin" and "this" sound like "t-thin" and "d-this" (Jenkins, 2009). Malay speakers tend to reduce clusters of three consonants to two, for example, /mps/ will be pronounced as /ms/ (glimpse /glɪmps/ → /glɪms/). The consonant /l/ is usually deleted in clusters of two consonants ("also /ˈɔːlsəʊ/" will be /ˈɔːsəʊ/). If the final consonant in clusters is /t/, /d/, or /θ/, it will be omitted, for example, "stand /stænd/" will be /stæn/. /v/, /z/, /ð/ and /dʒ/ will be devoiced in final position ("give /gɪv/" will be /gɪf/). /s/ will be voiced in medial and final position ("nice /naɪs/" will be /naɪz/), while /ʃ/ will be voiced in medial position ("pressure /ˈpreʃə/" will be /ˈpreʒə/) (Mesthrie, 2008).

Pakistan

Diphthongs tend to be long monophthongs in Pakistan English, for example, /əʊ/ and /eɪ/ will become /o:/ and /e:/ respectively (Raham, 1990). Pakistani speakers tend to lengthen short vowels (/ɑ:/ will be used to replace /æ/, and /u:/ is used to replace /ʊ/). Using a full vowel to replace a reduced vowel is another common feature of Pakistan English ("letter /letər/" will become /letʌr/). The diphthong /eə/ tends to be centring an closing and an /əɪ/ or an /ɑɪ/ is usually used to replace (Mesthrie, 2008). As for consonants, /θ/ and /ð/ are replaced by /t̪/ and /d̪/ (Kachru, 1992). /r/ is pronounced in all contexts, for example, ‘warm /wɑ:m/’ is pronounced as /wɑ:rm/. Retroflex stops are used in Pakistan English (/t/ and /d/ tends to be /ʈ/ and /ɖ/ respectively), for example, "dress /dres/" becomes /ɖres/. Also, there is no distinction between a dark and clear /l/. A clear /l/ is always realized (Mesthrie, 2008). The above-mentioned features are the features of native speakers of Urdo which is the national language of Pakistan (Ethnologue, 2002).

Nepal

In Nepal, speakers can hardly make distinctions between /s/, /ʃ/, /ʒ/, and /dʒ/. The /ɒ/ is replaced by /o/ and there is no difference between /ə/ and /ʌ/ (Vishnu, 2006).

References

Hiramoto, M. (2011). Is Dat Dog You’re Eating? Mock Filipino, Hawai‘I Creole, and Local Elitism. Pragmatics.

Hong Kong Government. (2016). https://www.bycensus2016.gov.hk/tc/bc-mt.html

Jenkins, J. (2009). World Englishes : A resource book for students (2nd ed., Routledge English language introductions series). London ; New York: Routledge.

Kachru, B. (1992). The Other tongue : English across cultures (2nd ed., English in the global context). Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press.

Lesho, M. (2018). Philippine English (Metro Manila acrolect). Journal of the International Phonetic Association: Illustrations of the IPA.

Llamzon, T. A. (1997). The Phonology of Philippine English. In Ma. Lourdes S. Bautista (ed.), English is an Asian language: The Philippine context. Sydney: The Macquarie Library.

Mesthrie, R. (2008). English circling the globe. English Today, 24(1), 288-32.

Rahman, T. (1990). Pakistani English. Islamabad: the National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-iAzam University.

Tayao, M. L. G. (2004). The Evolving Study of Philippine English phonology. World Englishes.

Tayao, M. L. G. (2008). A Lectal Description of the Phonological Features of Philippine English. In Ma. Lourdes S. Bautista & Kingsley Bolton (eds.), Philippine English: Linguistic and literary perspectives. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Trudgill, P., & Hannah, J. (2008). International English : A guide to varieties of standard English (5th ed.). London: Hodder Education.

Vishnu, S. R. (2006). English, Hinglish and Nenglish. Journal of NELTA.

Zuraidah, M. D. (1997). Malay + English = a Malay variety of English vowels and accent. In Halimah Mohd. Said and Keat Siew Ng (eds.), English is an Asian Language: The Malaysian Context (pp. 35–45).

Hits: 1032